2023

What’s new, Guest commentary

Atrazine: Latest science & policy analysis on a hormone-disrupting herbicide

Guest Post by Stacy Malkan

Atrazine is the second most widely used weed killer in the United States. Yet a significant body of scientific research suggests the herbicide harms the normal functioning of the endocrine system. In humans, atrazine has been linked to irregular menstrual cycles, abnormal birth weight and unexplained infertility. Animal studies have shown that atrazine may affect reproductive function in mammals, including estrous cycles, sperm motility, testosterone levels, and prolactin, luteinizing and follicle-stimulating hormone levels. In amphibians and various fish, atrazine has been shown to damage reproductive organs and systems.

Scientific research has also linked atrazine to birth defects—including gastroschisis and choanal atresia and stenosis—as well as breast cancer, neurotoxicity, slowed metabolism and respiratory problems. References and more details on all these health concerns are now available in a fact sheet written by my colleague Mikaela Conley at U.S. Right to Know.

More than a million people have read our fact sheets about chemicals of concern, showing there is a healthy appetite for science-based information about the health risks of food additives and pesticides. Unfortunately, scientific evidence alone doesn’t often lead to policies that protect public health, especially in the United States.

Banned in the EU but widely used in the US

The story of atrazine follows a common theme: decades of science raise serious health concerns, yet public health groups have been unable to convince the U.S. government to take action to limit exposures.

The European Union banned atrazine nearly two decades ago. But today in the U.S., more than 70 million pounds of atrazine are applied each year. Atrazine is applied to a wide range of crops here, including more than 65 percent of all corn crops, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. It is also used on lawns, sports fields and golf courses. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) notes that atrazine is one of the most commonly reported contaminants in groundwater and public drinking water.

Why is it so hard to take action in the U.S. to protect public health from hazardous pesticides? Corporate lobbyists and campaign contributions play a role. In 2022, the agribusiness industry spent more than $169 million on lobbying, with 1,311 lobbyists roaming the halls of Congress, according to OpenSecrets. More than 800 of these lobbyists were “revolvers,” meaning they are part of what OpenSecrets describes as a “revolving door that shuffles former federal employees into jobs as lobbyists, consultants and strategists, just as the door pulls former hired guns into government careers.”

The agribusiness industry also spends heavily on candidates running for office—from both political parties—with contributions topping $58 million in 2022. And that is just what we know about; the figure doesn’t include funds contributed through channels that are not disclosed.

The U.S. lags behind other countries in protecting public health

Campaign contributions and lobbying ensure weak pesticide regulations in the U.S. and a lack of political will to protect health. As Nathan Donley, a former cancer researcher specializing in pesticide policy at the Center for Biological Diversity, explains in a 2019 paper, the EPA has “all but abandoned its use of non-voluntary cancellations [of harmful pesticides] in recent years, making pesticide cancellation in the USA largely an exercise that requires consent by the regulated industry.” As a result, U.S. residents are exposed to more harmful pesticides than people in many other countries. At least 72 pesticides (including atrazine) that are banned or in the process of complete phaseout in the EU are allowed for use here. Brazil and China also have more health-protective pesticide restrictions than the U.S.

U.S. regulators are also operating with a huge knowledge gap when it comes to pesticide safety; the EPA does not assess health risks of “inert” ingredients in pesticide formulas—even though substances known to be dangerous, such as PFAS, are used as inert ingredients in pesticides. In a 2017 legal petition, the consumer watchdog group Center for Food Safety asked the EPA to close the loophole; the agency denied the request earlier this month. As the Guardian reported, “EPA says too many pesticide formulas exist to check all for the safety of ingredients that could harm humans, plants and wildlife.”

Corporate efforts to discredit science

The story of atrazine highlights another barrier to public health protections in the U.S.: The world’s largest chemical companies deploy many PR strategies to confuse the public, lawmakers and regulators about the harms of their products—and they sometimes fight dirty.

Last year, my colleagues and I analyzed a trove of internal Monsanto documents that reveal how the company ran its product-defense strategy for glyphosate, the world’s most widely used herbicide. The company’s own documents reveal their tactics for manipulating science, attacking scientists and journalists, and strong-arming regulatory agencies to keep glyphosate unregulated—-despite decades of science linking the toxic chemical to cancer, reproductive impacts, and other health concerns.

This report adds to a growing body of research and reporting on the deceptive tactics of the pesticide industry: the Intercept’s reporting on the PR spin to protect sales of neonicotinoids (the class of systemic pesticides driving the “insect apocalypse”) and detailing the tactics industry used to keep the deadly pesticide paraquat on the market for decades; or the New Yorker’s reporting on pesticide company Syngenta’s attacks on the scientist Tyrone Hayes.

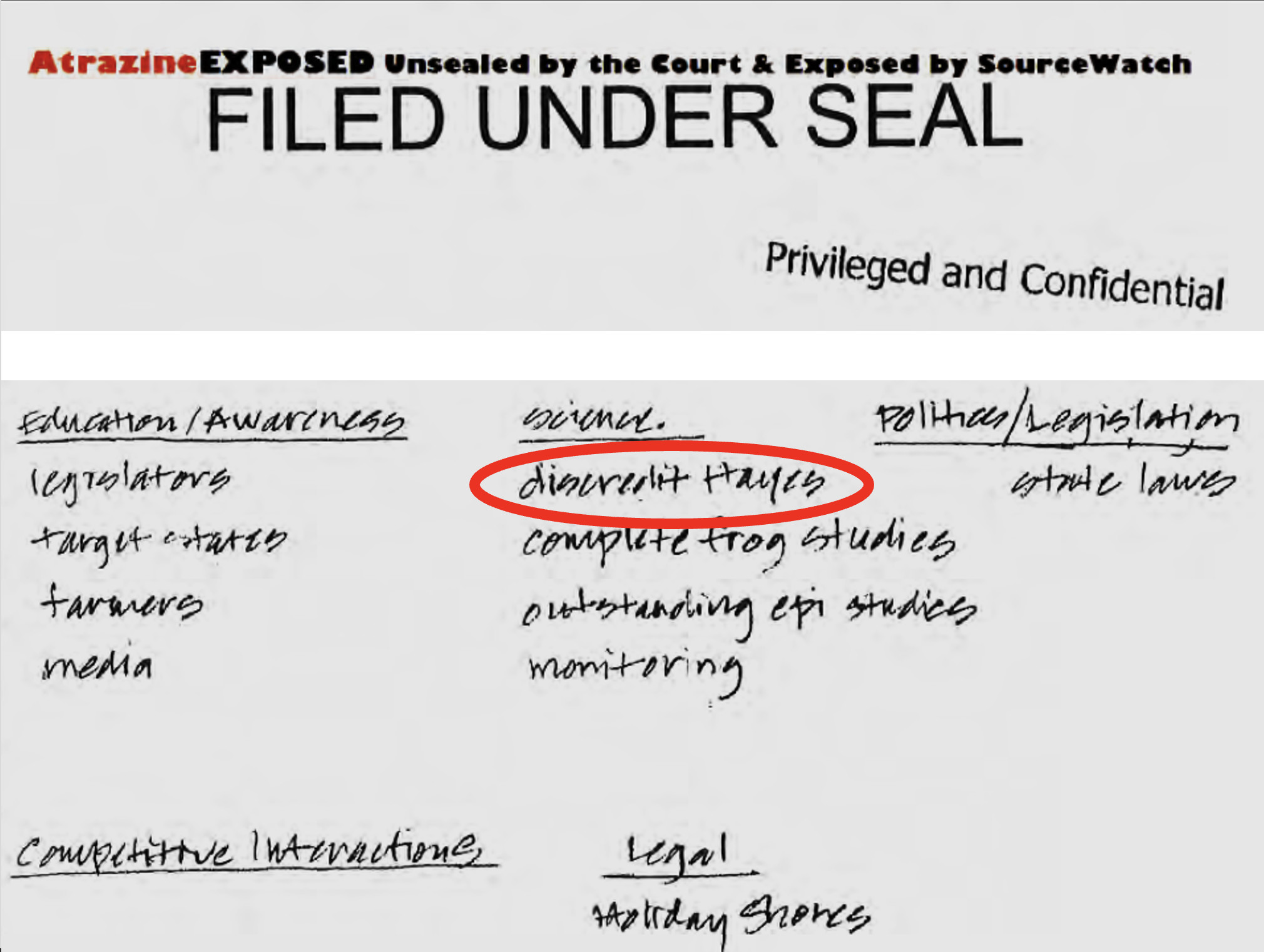

In a recent webinar hosted by the Collaborative for Health and Environment, Dr. Hayes explained how Syngenta, the manufacturer of atrazine, first hired him to research atrazine, then tried to suppress his research that found the herbicide disrupted the normal sexual development of frogs. As Rachel Aviv reported in the New Yorker, the company’s campaign to discredit Hayes included commissioning a psychological profile of Hayes to develop tactics to discredit him. One internal strategy memo described ideas to: “investigate wife,” “ask journal to retract” his research, and “set trap to entice him to sue.” In one hand-written note, a Syngenta employee wrote “discredit Hayes” as the company’s first goal listed under "science."

The tactics didn’t succeed in discrediting Hayes; his research helped inform the EU’s ban on atrazine, based on concerns about groundwater contamination and potential harmful effects on wildlife. And in May 2023, Hayes—a Professor of Biology and Associate Dean for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion at the University of California, Berkeley—was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in recognition of his distinguished and continuing achievements in original research.

In the atrazine story, scientific integrity scored a victory in the end; but unfortunately, not in the U.S. policy arena, where our farmers and our families are subjected to preventable exposures to toxic pesticides.

Stacy Malkan is co-founder and managing editor of U.S. Right to Know, a nonprofit investigative research group working globally to expose corporate wrongdoing and government failures that threaten our health, environment and food system. She investigates and reports on pesticide and food industry PR and lobbying operations. Stacy is author of the award-winning book, Not Just a Pretty Face: The Ugly Side of the Beauty Industry (New Society Publishers, 2007), and co-founder of the Campaign for Safe Cosmetics, a national coalition of health groups that exposed hazardous chemicals in personal care and baby products, and pressured companies to reformulate to safer products.