Note: This post contains distressing content

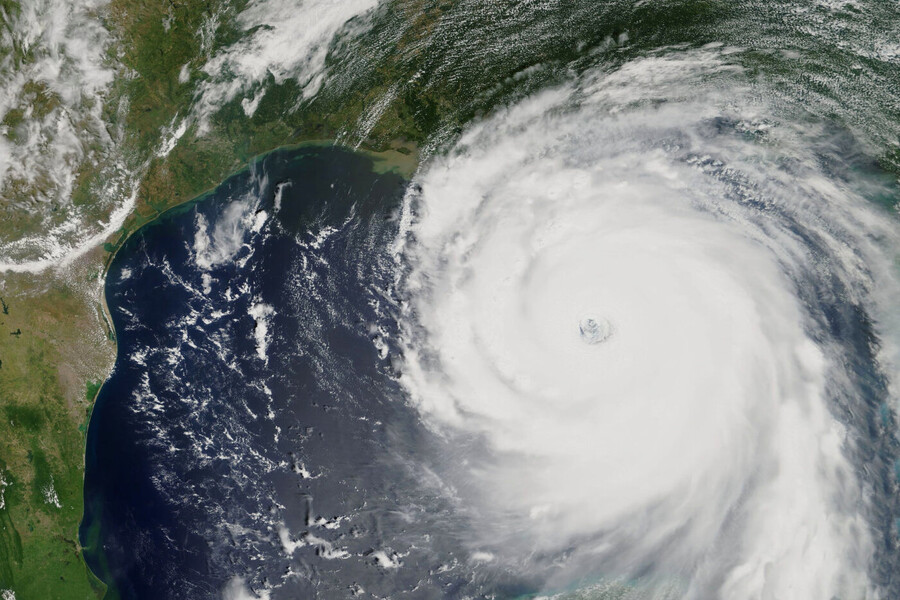

In August 2005, Hurricane Katrina made landfall and became the US’ deadliest and costliest natural disaster, displacing thousands of residents in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. Those who witnessed the devastation and survived carry the psychological toll of what climate change is capable of.

This year marks the 20th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, and climate change has continued to show itself in a myriad of ways. A growing number of individuals living in the United States experience ‘eco-anxiety’, a form of anxiety, distress, or grief associated with the awareness of potential environmental degradation.

Rising rates & disproportionate impacts of eco-anxiety

This form of distress is not to be mistaken for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Eco-anxiety is different from PTSD; just being in-tune and aware of potential cataclysmic impacts can impact anyone, even those who have not experienced a traumatic event.

Eco-anxiety is growing disproportionately amongst our most marginalized communities, with youth being particularly worried. For the survivors of Hurricane Katrina, at least 20% experienced some form of mental health issue following the disaster and many continue to live in flood-damaged homes and neighborhoods, affecting them daily.

As September is suicide prevention awareness month, it is important to talk about all the factors like stress, social support, and psychological perspectives that can influence our mental health, and how the environment that we live in can shape such factors. Without awareness of what factors into our mental health, many of our populations remain isolated and excluded from systems that should be helping them.

Effects on mental health of climate disasters - & heat

Effects on mental health are not isolated to Hurricane Katrina; they appear in climate disasters of all sorts. In fact, there are reported rates of 20-30% for depression and/or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in hurricane survivors overall, and similar rates have been seen in flooding scenarios.

On the opposite end of the weather spectrum, wildfires and droughts bring significant mental health burdens as well. In countries like India, climate events like droughts have increased the rates of suicides. As mentioned earlier, environmental threats affect low-income and minority populations more severely, with few publicly available resources to build back up after a disaster.

Some environmental changes don’t even need to cause acute destruction to have a lasting toll on an individual’s health. The best example of this is changes in the heat index – increasing environmental temperatures correlate with increasing rates of aggression, whether that is to oneself or others. Especially for people with pre-existing mental and physical disorders, medications may contribute to additional intolerance to heat and environmental change.

At the very least, long-term temperature changes have led to increased self-reports of ‘bad mental health days’ from the general population.

Pressing for resources & action

While awareness on the topic of climate disasters and its impact on mental health is important, it is more crucial to understand how our governments and policies can protect the environment and our health.

Treatment and program costs for mental health support services in the US have been increasing over time, and yet continue to face budget cuts. Especially for individuals with limited insurance plans or those who rely on Medicare/Medicaid, the reality of limited healthcare is bound to have a detrimental effect. Medicaid is the largest payer of mental health services in the United States and it also acts as the primary form of healthcare coverage for low-income individuals in the country.

As the climate crisis is fueling increased mental distress and mental illness, we separately need more mental health resources to support our communities. At this moment of escalating need, the current administration has passed legislation (P.L. 119-21) which cuts a trillion dollars from the US healthcare system, the largest cut in history.

Engagement is critical

Despite the negative trend of support for mental health initiatives, it is critical that our communities advocate for preserving and improving mental health services for all. Beyond that, individuals can address their own eco-anxiety by joining their local green community.

Many local organizations host events and seminars to spread awareness and make active changes in their neighborhood, like clean-ups and advocacy groups. Eventually, many of these groups can have lasting impacts by legislative change.

Engaging in the community is a tool to gain back control of our green spaces and mental health, and the time is now to act to make eco-anxiety a word of the past.

Roya Abedi is a medical student at Georgetown University School of Medicine. She has held several roles, including her position as a health care analyst at the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), where she was responsible for project support, communications, targeted literature review, and environmental scans. She has experience in research management and coordination, particularly in the areas of rural health and environmental health. Prior to joining NCQA, Roya was a research associate at the Northern Ontario School of Medicine, where she supported and managed research projects related to rural health care in Canada and internationally.