Asthma Research and Resources

Asthma DataData from the US dominate this discussion because global data are sparse and often not very recent. We acknowledge that asthma is a worldwide issue and present data that we can find from reliable sources. |

Asthma is a chronic lung disease that affects hundreds of millions of people—estimates are between 223 and 334 million worldwide.1 Asthma often leads to a reduced quality of life due to both physical effects and also psychological and social effects, burdening individuals, families, schools, employers and government. Environmental exposures play a significant role in the development of asthma and as triggers of asthma episodes, called asthma attacks.

Asthma is a growing burden in low- and middle-income countries which previously had low rates, and where most asthma-related deaths occur.2 In some wealthier countries, asthma has remained static or declined, but in others, including the US, prevalence has been increasing for reasons not fully understood, although environmental factors likely play a role.3

Asthma Prevalence and Trends

Asthma has a global distribution with a relatively higher burden of disease in Australia and New Zealand, some countries in Africa, the Middle East and South America, and northwestern Europe. A 2014 report concluded that asthma symptoms became more common in children from 1993 to 2003 in many low- and middle-income countries, which previously had low rates.4

In the United States, about 24.6 million people, including nearly one in ten children, currently have asthma.5 Total costs of asthma in the US were estimated at approximately $56 billion as of 2007, including direct medical expenses, lost school and work days, and early deaths.6 According to the American Lung Association, asthma is one of the most common chronic disorders in childhood and a leading cause of hospitalization in children, as well as one of the leading causes of school absenteeism.7

|

data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;8 click to zoom |

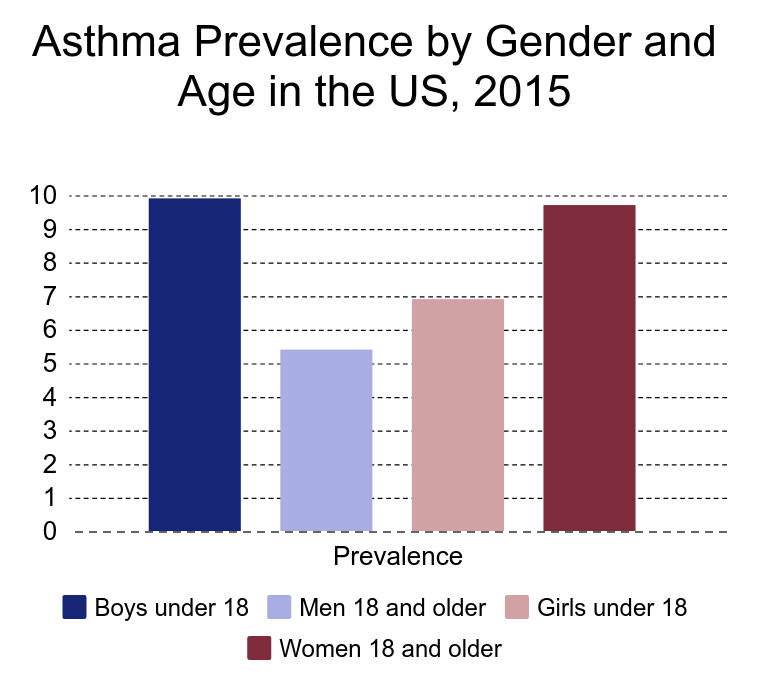

Rates of current asthma among adults and children in the US increased significantly from 1980-2010, including a doubling in childhood rates from 1980-1995. More recent trends have not yet been described. In 2015, current asthma affected 7.8 percent of the US population, about 24.6 million people. The rates were higher among children under 18 overall (8.4 percent) than in adults (7.6 percent). Females (9 percent) in the US experience asthma at greater rates than males (6.3 percent).9

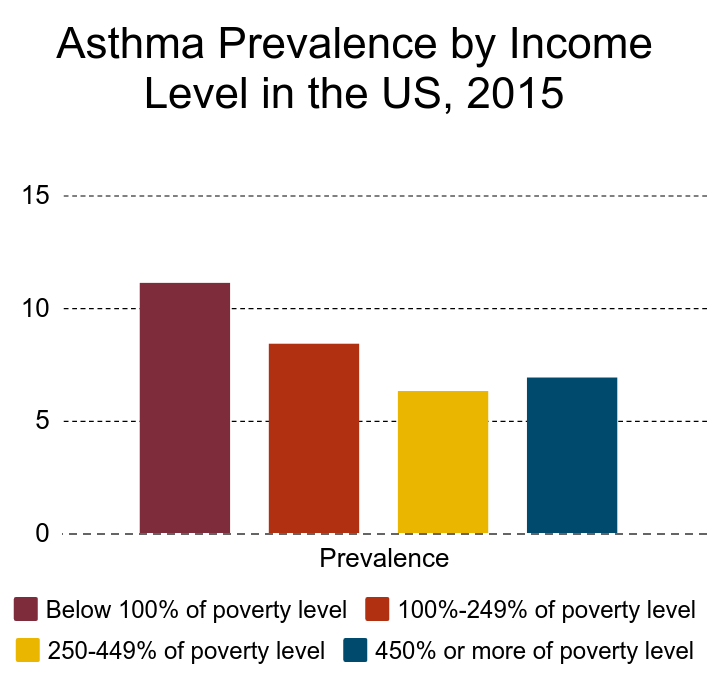

In the US, racial and socioeconomic disparities with regard to asthma are dramatic.10 The prevalence of asthma is higher among persons with family income below the poverty level.11 Compared to White children, Black children have higher rates of asthma (13.4 percent), and national prevalence rates for children of color have climbed more steeply than prevalence rates for White children.12 Black children are hospitalized for asthma at higher rates than White children, and their asthma is more severe.13 Increasingly, asthma leaders consider these disparities to be inequitable—they are not only unequal but also fueled by factors and conditions that are unjust. Asthma disparities by race hold true across economic strata and in urban as well as rural communities.14 Higher exposures to structural, social and environmental risk factors contribute to these inequities. In some places, people experiencing higher rates of asthma have less access to high quality asthma care.15

data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;16 click each to zoom

Asthma Origins: A Multifactorial Disease

|

A Story of Health includes Brett's Story regarding asthma. Click to open the PDF. |

Typically, people with asthma experience recurrent attacks of breathlessness, wheezing, chest tightness and coughing. The underlying process includes inflammation of the airways, reversible obstruction of the flow of air in and out of the lungs, and the tendency of the airways to overreact to stimuli. Though people with asthma have similar symptoms, the origins and triggers of the disease may differ considerably from person to person.

Multiple factors contribute to the development of asthma. Those factors include these:

- Genetic predisposition, often manifested in a family history of asthma or allergies

- Exposures in the home, school, workplace or outdoors to environmental agents, including chemicals in products or released into the air, and biologic agents, such as some viruses and allergens.

- Some social determinants of health, including obesity and psychosocial stress, along with dietary factors, have also been implicated in the development of asthma. Increasingly, asthma leaders in government, academia and communities are identifying structural racism as a root cause of many of the conditions that contribute to elevated risk factors for asthma.17

Environmental Factors in Asthma

Asthmagens are those agents that act in combination with other factors to initiate or cause asthma in someone who did not previously have the disease. Asthmagens may be encountered in the workplace, at home, at school or elsewhere. They are generally categorized based on the pathway by which they initiate asthma.

- Sensitizers: Also known as allergic or immunologic asthma. Agents include biologic agents (such as pet allergen, mold, dust-mite, and cockroach allergens) or chemicals such as gluteraldehyde (found in some cleaning agents). This is the most common form of asthma and is strongly linked to family history. Sensitizer-induced asthma is characterized by an asymptomatic period of sensitization. Although the immunologic mechanism is not known for all agents, many sensitizers (allergens) produce asthma through an immunoglobulin E (IgE) mediated mechanism.

- Irritants: Asthma develops most often from relatively high one-time exposures to agents classified as irritants (for example, tobacco and irritant chemicals such as acids). Irritant asthma does not involve the immune system, although individuals may experience the same symptoms (coughing, wheeze, breathlessness, and so on) triggered by bronchospasm. Since irritant asthma is not mediated by the immune system, allergic sensitization does not occur, and asthma may be caused from a single exposure to the irritant.

After asthma develops, exposures to a variety of allergens or irritants can trigger or exacerbate an asthma attack.

Causes of asthma (substances or conditions that contribute to the development of asthma) are distinct from triggers of asthma (those things that cause an asthma attack, or make it worse). Many risk factors are capable of both initiating new-onset asthma and triggering asthma attacks. For example, tobacco smoke and traffic-related air pollution can both cause the initial onset of asthma in people who previously did not have the disorder, as well as trigger asthma attacks in people already diagnosed. In the case of allergens, exposures in early life (pre-conception through infancy) may protect against the development of asthma, whereas those same exposures for a child with asthma can cause asthma attacks.

Just as a different mix of risk factors may have contributed to the development of asthma in one person versus another, individuals also differ in the exposures that will trigger an asthma attack.

Environmental Risk Factors for the Development of Asthma

|

image from Joshua Miller at Creative Commons |

The strength of the evidence for the causal role of environmental risk factors in new-onset asthma varies, especially as it relates to age and timing of exposure. Environmental exposures associated with the initial onset of asthma include these:

- Tobacco smoke (for both the smoker and non-smokers exposed to environmental tobacco smoke)

- Various biological allergens (for example pests, pets, dust mites and some species of mold28 )

- Chemicals (including cleaning agents such as bleach and gluteraldehyde)

- Traffic-related air pollution.

There is solid evidence that psychosocial stress and obesity29 —both of which can derive from environmental exposures and conditions—also contribute to the development of asthma. Traffic-related air pollution and psychosocial stress are discussed in more detail below.

Although many chemicals shown to cause asthma in workers have not been studied in other populations, they can likely also cause asthma in settings outside the workplace. For example, formaldehyde levels are positively associated with childhood asthma.30 Working parents can also bring exposures home to children on clothing and in other ways, and so parents and pediatricians should consider occupational exposures when assessing causes and triggers for children.

Environmental Risk Factors for the Exacerbation of Asthma

Many substances that can cause new onset asthma can also trigger asthma attacks in people with the disease. Environmental risk factors that exacerbate asthma symptoms include these:31

- Chemical sensitizers and irritants used in manufacturing and other workplaces

- Tobacco smoke, and outdoor air pollutants that infiltrate the indoor environment

- Some pesticides

- Allergens including mold, pollen, cockroach droppings, and dander from pets and rodents

- Exercise and cold weather

- Outdoor air pollution, including traffic-related air pollution and also pollution from industrial sources

- Family and community stressors/psychosocial stress

Interactions among different exposures may be important in the exacerbation of asthma. For example, a 2003 study found that asthma symptoms in children ill with a respiratory virus are likely to be more severe if the children are exposed to nitrogen dioxide, even at levels below current air quality standards.32 In a study from 2011, combining exposure to low levels of pollen with exposure to levels of pollutants commonly found in urban air dramatically worsened asthma symptoms.33

Traffic-Related Air Pollution and Asthma

|

image from Luc at Creative Commons |

TRAP (traffic-related air pollution), is a complex mixture of particulate matter derived from combustion, non-combustion and primary gaseous sources. Increasing evidence suggests that long-term exposures to traffic-related air pollution and its surrogate, nitrogen dioxide, can contribute to new-onset asthma in both children and adults.34 Components of diesel exhaust may also cause asthma,35 shown by studies finding that children growing up along streets with heavy truck traffic are more likely to develop asthma-related respiratory symptoms.36

Although the evidence base supporting a link between traffic-related air pollution and new-onset asthma is relatively new, exposure to vehicle exhaust and other forms of air pollution is well established to trigger asthma attacks in people with the disease. Common air pollutants that exacerbate asthma include these:

- Ozone

- Nitrogen dioxide

- Sulfur dioxide (from vehicles that burn fuels with a high sulfur content)

- Particulate matter (PM2.5)

Climate Change, PAHs, Outdoor Air Pollutants and Asthma

As carbon dioxide (CO2) levels rise and temperatures increase due to climate change, both ground-level ozone and airborne pollen levels are increasing. The combination of higher levels of asthma-related air pollutants associated with changes in atmospheric conditions is expected to continue to increase the frequency of asthma attacks in people with asthma. These conditions may also increase rates of new onset asthma.

Effects of climate change on asthma:

- Increases in levels of ozone and fine particulate matter can trigger inflammation of the lungs and reduce lung function, causing chest pain and coughing.37

- Increasing carbon dioxide concentrations affect the timing of allergen distribution, amplifying the allergenicity of pollen and mold spores.38

- Longer growing seasons for allergens will produce more airborne allergens and could lead to more asthma attacks worldwide, including for 10 million Americans with allergic asthma.39

- Increasing precipitation due to climate change can increase mold spores, an asthma trigger and a likely risk factor for the initial onset of asthma.40

- Increasing frequency of droughts can increase dust and particulate matter, which are both causes and triggers of asthma.41

- Increasing wildfire activity due to global temperature changes could exacerbate asthma and increase asthma emergency department and hospital visits.42

Family and Community Stressors/Psychosocial Stress

Family and community stressors such as financial problems, divorce, exposure to violence at home or in the community, and systemic and structural racism can make children more susceptible to many health problems, including asthma. There is solid evidence that psychosocial stress contributes to the initial onset of asthma, especially when combined with other risk factors. Stress can also trigger asthma in people with the disease.

Stress can add to and even magnify the impacts of exposure to other environmental conditions that foster the onset or increase the severity of asthma. For example, children in relatively low-income families who are also exposed to traffic-related air pollution are at greater risk of frequent asthma symptoms than children in the same neighborhoods whose families are financially better-off.43

Protective Factors

Certain environmental exposures and conditions can protect against onset or symptoms:

- Exposure to microbial diversity in the perinatal period may diminish the development of asthma symptoms.44

- Breastfed infants are less likely to develop asthma and allergies compared to those fed infant formula.45 Breastfeeding enhances immune function.

- Higher vitamin D intake during pregnancy is associated with decreased risk of wheeze in early childhood. Reduced risk of wheezing may be due to reduced frequency of respiratory infections.46

- A healthy microbiome full of good bacteria and other microbes promotes the immune system’s ability to fight off pathogens. Broad exposure to a wealth of non-pathogenic microorganisms early in life is associated with protection against many health conditions. Studies have found that first-year infants exposed to house dust high in levels of mouse, cockroach or cat allergens along with a variety of bacteria report significantly lower rates of allergies and recurrent wheeze at age three.47

Prevention Strategies

National Asthma Management Guidelines detail how to prevent asthma attacks in people who already have the disease (“secondary prevention”). These guidelines include

- Regular assessment and monitoring

- Medications appropriate for the severity of an individual’s asthma

- Education for self-management

- Understanding and addressing co-morbidities

- Reducing exposure to environmental triggers

Because these elements of effective prevention of asthma attacks include both medical interventions and interventions in home, school, work and community environments, integration of clinical care with community resources is essential. Various models for integrating clinical and non-clinical interventions have proven cost-effective, including community health workers providing in-home asthma education and environmental trigger reduction.48

There are also promising strategies for preventing new onset asthma. These include clinical interventions and interventions that reduce known risk factors for the development of the disease. Current priorities of the National Institutes of Health for clinical trials include these:

- Prevention of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and other early-life infections

- Immune modulation using prebiotics, probiotics, immunostimulants and animal exposure

- Prevention of allergen sensitization and allergic inflammation, using anti-IgE

- Environment and behavior

Environmental, Behavioral and Social Interventions to Prevent Asthma Attacks and New Onset Asthma

Preventing Asthma Attacks

As noted above, reducing exposure to environmental triggers for asthma is a critical element of preventing asthma attacks for people with asthma. Not everyone is sensitive to the same environmental triggers, but once an individual knows which triggers exacerbate her asthma, minimizing exposure is the best strategy. Some environmental triggers are within the individual’s control (for example, pets in a home); others—for example mold caused by a landlord’s failure to fix a persistent leak, or air pollution from a nearby bus depot—require action and advocacy by others.

Preventing New-onset Asthma

Because asthma is a multifactorial disease, the origins of which may vary from person to person, multifactorial interventions are likely to be most effective at preventing new onset asthma at both the individual and population level.

A Cochrane review of seven studies targeting women at high risk of having a child who develops asthma concluded that nutritional interventions combined with environmental trigger reduction reduced the risk of the child developing asthma by 50 percent; the review also concluded that multifactorial interventions were more effective than single-factor interventions.49

A 2015 Lancet review concluded that until the base of intervention evidence is stronger, “public health efforts should remain focused on measures with the potential to improve lung and general health", such as these:50

|

image from Brandon at Creative Commons |

- Reducing tobacco smoking and environmental tobacco smoke exposure

- Reducing indoor and outdoor air pollution and occupational exposures

- Reducing childhood obesity and encouraging a diet high in vegetables and fruit

- Improving feto-maternal health

- Encouraging breastfeeding

- Promoting childhood vaccinations

- Reducing social inequalities

Following this guidance, a recent process in Massachusetts identified four priority risk factors with specific exposure reduction recommendations for individuals to help prevent asthma:51

- Smoking (including environmental tobacco smoke)

- Parallels current recommendations in asthma management programs (cessation support, smoke outside/not in cars)

- Traffic-related air pollution

- Limit time outdoors if the air quality is unhealthy.

- Avoid exercising near high-traffic areas. Find alternative routes to walk to school (see our Built Environment webpage for more information.)

- Consider using a HEPA air filter in the home.

- Obesity

- Talk to a medical provider about weight-loss strategies that are best for you.

- Strategies include routine exercise, reducing the amount of fast foods and sugar-sweetened beverages in your diet and eating more fruits and vegetables. (When exercising, avoid high-traffic areas.)

- Occupational asthmagens

- Federal safety laws require your employer to provide a safe and healthy workplace.

- If you feel that your workplace is unsafe and needs a confidential health and safety evaluation, you can contact OSHA or state departments of labor standards.

These risk factor-reduction recommendations are based on expert judgment about the strength of the evidence that particular risk factors contribute to asthma onset, along with thoughtful consideration about the pros and cons of taking action when there is inherent uncertainty about how risk factors interact with individual factors to cause disease.

However, individuals alone cannot control exposure to risk factors for asthma onset. Policy changes and program investments are needed to reduce environmental contaminants in workplaces, homes, schools and communities—with a particular focus on populations and neighborhoods that are disproportionately exposed—if we are to begin to reverse rising rates of new onset asthma. Such initiatives will also benefit people already living with the disease.

See more about environmental contributors to asthma in the list of CHE publications and Dig Deeper resources in the right sidebar.

This page was last revised by student intern Jessica Hale with Maria Valenti, Ted Schettler, MD, MPH, Polly Hoppin, ScD, and Molly Jacobs, MPH, plus editing and graphics by Nancy Hepp, in November 2017.

CHE invites our partners to submit corrections and clarifications to this page. Please include links to research to support your submissions through the comment form on our Contact page.